So…

In my business, we work with a partner who handles part of the highly technical equipment we sell. I’ve worked with a couple of different partners, and since it is such a critical issue that you get in sync, I try to do something that officially kicks off our business relationship. One time, I had a guy over for a nice dinner at our house. Another time, I wrote a note. And then there was my most recent partner…(he has a rather unfortunate last name which has been quite fun for the more sophomoric among our company: Bates). When Bates and I started working together, I bought him a book “Zig Ziglar’s Secrets of Closing the Sale”—a nice hardback edition—I wrote a dedication to him in the front that said something to the effect of “I look forward to working with you, blah blah blah.” The book is great! Although a little dated and sometimes breaks into “rah rah sisk boom bah!” trying to motivate you, it contains a lot of great principles and the psychology behind the sales process that is very useful for persuasive selling. Bates had absolutely no sales experience, so I knew it would be a useful reference…if he read it.

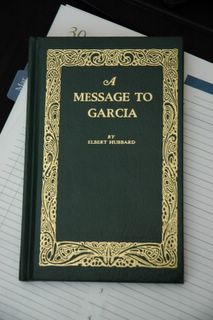

Bates reciprocated with a fantastic gift—a beautifully bound version of the pamphlet A Message to Garcia

by Elbert Hubbard. Somehow, in all my goal-setting mania and management guru-ism I had never encountered this work, and when I read it, I was truly inspired. When he gave it to me, Bates told me: “I hope it will give you some insight into what motivates me.” I had known him for a few years, and I believed him.

If you haven’t read the book, it only takes about 10 minutes to read, and is worthwhile. In essence, it praises Rowan, a soldier who was given a message to deliver during the Spanish-American war. He didn’t turn around and ask stupid questions, he just went out and got the message delivered, although the recipient, Garcia, was holed up somewhere unknown in the jungle. Rowan just figured it out and got it done.

The story uses this example to illustrate the difference between people who “just do it” and the more popular philosophy (which apparently dates back at least 100 years) of responding with idiotic, cow-like facial expressions, dumb questions, and essentially placing the burden back upon the person requesting that the work be done. As a manager in my previous job, this common behavior is very frustrating to me and the book’s challenge really struck a chord. Bates was shaping up to be more than meets the eye, and I looked forward to working with him.

Here’s an unusual fact about our job—a lot of times the customer relies on us to know what we’re talking about (they actually don't learn all about it before they buy). They want us to be competent and give them recommendations which we know will work and then to stand by them. I can safely say that, once a person knows what they are talking about, which usually takes 2-3 years in our industry (yes, really), you win about 80-85% of the orders because the customer relies on you to take care of them—it works great…once you know what the hell you are talking about.

The downside is that there is a HUGE temptation to fake your way through—and it can be done pretty convincingly…for about 20% of our customers. The other 80% won’t tell you that they know you are full of shit; they just don’t buy from you. I’ve observed as rookies go and wholeheartedly B.S. their way through a meeting and feel like it “went great!” then are truly perplexed when they don’t get the order…customers tend to be conflict-averse so they just don’t let you know that they don’t trust you or want you to handle their job. You just figure it out when you see competitor’s boxes sitting out in the hall…

When people in my business don’t know what they are talking about, it reminds me of “duckspeak” in Orwell’s 1984. Here’s what it sounds like: “wha wha wha wha blippity blap. It also has the capability of mwha hoompa doompa diddly doo.” Unfortunately, that’s also what calculus sounds like to me--kinda like the adults in Peanuts (I remember sitting back and just listening to the wacky cadence of pure calculus mumbo-jumbo eking out of the visiting professor from Germany.)

The remedy for this inherent ignorance when you first start is to assume a position of learning—LISTEN to what people are telling/asking you--if you don’t know, tell the customer and WRITE DOWN what they need to know and LOOK IT UP. Then FOLLOW UP with them and give them the correct information. It buys you a bunch of credibility. Our customer base is made up of mostly engineers and scientists. Here’s how the scientific method works. Come up with a hypothesis. Design an Experiment. The goal is to DISPROVE the hypothesis. Therefore, if you present yourself as the omniscient Master of all Knowledge, their goal is to knock you off your pedestal.

Here’s my sneaky side again—if a customer has a series of complex questions, sometimes I get the hint that they are seeing if I am one of these know-it-all smart-asses. Even if I know the answer, I will write down their question and not answer it right away. Then I will come up with a “home run” answer for them and Email it to them. Besides, it gives me a pretense to contact them again…

So…as you can probably figure out by now, Bates was one of these BSers. He was so anxious to set the world on fire that he immediately had the urge to sell from a position of high competency. An irritating aside is that he would run an average of 3.5 hours late…all the time. One time we had a demonstration at 9:00 AM and he showed up at 4:30 PM, saying “Sorry, I got caught up and couldn’t get out of the house.”

Another tragically funny time we did a demonstration on a technique called image deconvolution. It uses a series of complex algorithms (mathematical formulas) to numerically characterize images and perform calculations with the picture components to make the image clearer. I had talked to the customer and we had determined that this would be very helpful to his research. The day of the demo came and it was Bates’ job to run the computer and input the data for the calculations. He was very excited about it and was determined to make a grand slam of the demo. The customer invited 15 observers from across the institution to see the data we generated. I even anticipated the crazy-lateness and went to Bates’ house to pick him up (if only I had a short bus available….)…They all stood by and watched Bates take apart his computer for an hour. Just when I was down to my last knock-knock joke (just kidding—I actually brought some other equipment just in case something happened, but had shown everything I could there, too), he got it up and running. He then processed our images for another hour…An HOUR! (For reference sake, it usually takes 20 seconds.)

Have you ever watched over someone’s shoulder as they work on the computer—equivalent to paint peeling, grass growing….you get the idea.

Hey, dude—we are actually trying to SELL SOMETHING here!

Finally, after an hour, we produced an image that looked….like mud. Not Good. 14 of the 15 people left. The other guy was just hanging out to watch the train wreck…and he wasn’t disappointed. Bates chugged along on the algorithms for another hour. Then another. After a total of 4 hours at the demo, he looks up and says the following: “You know, deconvolution is really overrated sometimes. People think it is a cure-all, but it seldom works very well. After looking at these samples, it is very clear to me that you need to (buy something that costs $110,000) (deconvolution costs $3500).” So, during my instantaneous heart attack, the customer, who is a very nice,soft-spoken Canadian guy, just completely lost it. He told Bates “Whatever you are doing there, just stop it. Pack it up, and get out! I don’t want it.” To toot my own horn, I later closed the sale for the order in spite of this. Turns out Bates, despite a month’s notice, had NEVER performed image deconvolution in his life prior to that day, and he was just making up numbers to plug into the complex equations.

The lesson: Hubbard apparently left out the part about preparation, competence, honesty, and freakin’ common sense.

The Odyssey with Bates went on for over a year. We never made one sale as a team, which is incredible. I tried very hard to stay in a positive frame of mind with him. I’m pretty hesitant to be critical just flat out and direct to a person’s face, but I fought the urge to avoid this and would make appointments to meet with him outside of work to discuss our team selling methods very candidly and as constructively as possible. We were even pretty good friends. His manager had never observed him in front of customers (a huge downside to our company, which trusts its employees to be competent—more like, “we don’t take the time or expend the energy into managing our employees”).

Finally, the jig was up and we were confronted with our lack of success. My response to the manager was “Somebody needs to come to a demonstration with us and see what happens! It’s often a confusing mess where buying the product from us is not the next logical conclusion (to me this is the definition of the sales process)…Just come and see what happens for yourself—I just want to make sure it’s not me!”

And I did something that was pretty tough—I called Bates and told him exactly what I told the manager. I thought this was the moral high ground, although I knew he wouldn’t be happy. I just hate the back-stab crap that usually happens.

But I overestimated his maturity, and I looked like the asshole who was just stirring up trouble and not taking accountability.

So the manager, rather than expending any effort and doing what I suggested concluded “(me) and Bates just can’t work together—they are incompatible.” It was interpreted that I am maybe a little too demanding and difficult to work with (okay, I’ll concede a little of that). But I had the track record as the #1 guy in the company, so I got at least a little bit of benefit of the doubt. Bates was moved to 2nd-tier accounts, I was given another guy to work with (a seasoned veteran), and we have only spoken briefly since then. My new guy and I have closed 100% of our demonstrations—but Bates has done okay since then, too.

Maybe we were incompatible (I just refuse to accept this explanation—I’ve been successful with people that I absolutely hated—they just didn’t know it).

Maybe it was the wrong thing to do to warn Bates about my conversation with his boss

Maybe, as the senior employee, I should have assumed more of the burden on myself for our demonstrations

Maybe I should have been more openly critical earlier in the game—I’ve since found out that Bates’ current partner frequently calls him up, cusses him out, threatens him about being late or not being prepared, and they get along great! I just don’t see myself doing that with another grown man!

In other words, did I enable him by covering his ass while hoping he would become more competent or come to some sort of realization about the right way to handle customers.

I also think I fueled the flames by mentioning other people who were successful in his position and what they did that made them successful. His arrogant personality made him turn from that and try to invent a different method. Clearly, it was a complicated psychology--while I'm obviously not responsible for it, should I have handled it differently?

Maybe there is a complex interaction of parameters, such as the fact that Bates has matured after his first year, combined with a chance to start over with another person.

Maybe his BS works better with 2nd tier accounts where the customers are less educated and discerning

Is it helpful to reflect back on these things? I think so.

What would Rowan have done?

At any rate, this time the message didn't get delivered...

No comments:

Post a Comment